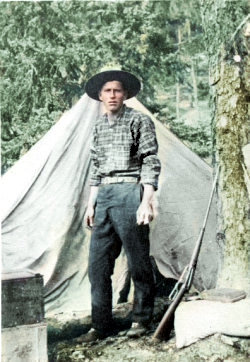

Fred has aged slowly. He gave me a photograph of himself marked simply, "PFL (Poorfish Lake) 1927." It is late summer. Fred is standing beside a large, rough-barked black spruce which is a veteran of perhaps two centuries. Fred is a slim, short figure, looking intently into the camera. He is twenty-seven years old, but he still has an unlined, boyish face, so that one might think him eighteen. He is wearing a ranger-style felt hat, similar to those worn by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, a check shirt, ordinary blue denim pants and beaded moccasins. It is a typical summer campsite on the canoe route, with gear piled here and there. His pocket watch hangs from a tree limb overhead, and his rifle, a long-barrelled lever-action model, stands propped against a tree. On a sack of white flour rests his camera case. Two wooden grub boxes are stacked on the ground beside him.

Between the fall of 1923 and the spring of 1940, he trapped every fall, winter and spring, except for the winter of 1932-33, when he operated a trading post. After 1940, Fred operated a sawmill for a time in Flin Flon, Manitoba, in partnership with his brother Edgar. By 1947, Fred was back in the bush, and he trapped every winter between the fall of 1947 and the spring of 1957. Then for three winters, he was involved in managing his own mink ranch at Ile-a-la-Crosse, but he got back to the North for both the spring and fall catches in 1961, 1962 and 1963. Since then Fred has trapped: in the fall of 1965 and 1969; in the spring and fall of 1973. Combined, these seasons amount to thirty-three years of trapping. Fred is a loner; whereas Ed Theriau, on encountering the trails of dog teams in the bush in mid-winter would follow them, and seek out, if possible, his Indian neighbours; Fred, if travelling in new country, would probably veer away from the trail to avoid them. His preference has always been to operate alone. There is no evidence that he ever had a partner other than Ed for a few seasons, and Tom Beads for one fall. The occasions when Ed and Fred met in winter are faithfully noted by Fred. There is often only one such entry in an entire winter; sometimes there are two. There are seasons in which he does not mention Ed at all. Mail service to Poorfish Lake was almost non-existent. The Hudson's Bay Company post managers did the best they could to forward letters they received. Sometimes they held a letter until the trapper to whom it was addressed appeared there in the spring. Or they might forward the letter to an outpost that he was expected to visit during the winter. If the outpost was only a temporary one, a letter might be left there when the place was closed for the summer. That outpost was not necessarily re-opened the next year; if fur-bearing animals were scarce in that territory the outpost might remain closed for several years, and any letters left there would be forgotten until the outpost was finally re-opened. By some such mix-up, Fred Darbyshire received the last letter that his mother wrote to him more than six years after her death. In the early years, there were no printed maps available to Fred and Ed, Even when the maps, in due course, were issued by the government, many of the lakes, rivers and creeks were without official names, as they are to this day. In the meantime, Fred and Ed, for their own purposes, gave many of the local physical features names suggested by some outstanding characteristic, by something seen nearby or by some local event. They named Beads River after Tom Beads, Gun Creek after Joe Gun, a Chipewyan acquaintance, and Horrible Lake for a particularly hard trip over its slush-covered surface. They also named Silt River, Tamarack Creek, Stone Creek, Roaring Creek, Black Bear Rapid, Grassy Creek, Burnt River, Caribou Creek, Old Man Lake, Coyote Lake, Island Lake, Halfway River, Moose River and many more. One night Fred camped on a small creek and read, by firelight, in a 1932 issue of Liberty Magazine, an expose of one Gaston B. Means. Thus the creek became B.Means Creek and is ever afterwards so denominated in Fred's records. Although a less qualified person to be so honoured would be difficult to find, the name is unique for that reason. Fred is an expert moose hunter. His diaries refer often to the time and effort he has spent calling moose in the rutting season. Often he has spent weeks at it, paddling the still lakes by moonlight, and calling from favourite blinds. And some seasons he has had no success. In 1948: "I called up a moose, no fat on him. That same night another bull stopped me in the Roaring Creek Narrows." In 1950: "I called up a gentleman moose at two am, not very fat." 1951: "I had a wonderful steak this evening, worth a buck and a half." "A moose came to visit us tonight. A big bull, it was only a dozen yards away. I have meat so did not shoot." 1956: "The country seems devoid of big game." 1961: "I went out calling in the evening. I called up nothing, but I saw a fat cow moose swimming across the lake. I surely made a blunder there. I fired three shots at her and missed each time. Then I let her get to shore. My rifle jammed, the first time a gun ever failed me. I now have a rifle for sale cheap." "I do not care much for bear meat," is one comment in Fred's Diary. From various other entries, it appears that bears were more often an annoyance to him than a blessing. Late one fall Fred was hanging fish to use as winter dog food. The weather was warm, and the stink of fish was strong all around his log cache, and far downwind.

A brief diary entry closes the story: "That bear finally got what he was looking for, I have him hanging up in the fish cache." Encounters with bears were most common in the fall. In September 1953: "A bear came fooling around the tent last night. I fired some shots at it in the dark. When I went looking for it in the morning I found it lying about one hundred yards away, in some bushes. Thinking it was dead, I walked up to within four feet of it. Then it moved out of there in a hurry. It was a very foolish thing for me to have done," In September of the next year: "A bear came to the tent while I was busy with the fishnets. He stole a big jackfish that I had hanging from a limb. I could have seen it had I looked up from my work." On December 13, 1953: "A bear ate a mink out of one of my traps," although any bear, by general rules and standards, should have been in hibernation by this time. These are only a few of the many references that suggest why Fred came to consider bears generally as regrettable nuisances. I asked Fred to share his knowledge of the fish runs that fill the lakes and rivers of this country in autumn. "Spawning time varies from lake to lake," he answered. "At my favourite spot below a certain rapid, the whitefish are usually on hand on the seventh day of October. On this date, I made a point to be on hand, too. The time of arrival never varied more than a day or two, year in and year out. They began to thin out about two weeks later, around the twentieth of October. In some of the lakes, they would be spawning as late as the fifteenth of November. In other spawning creeks, I have seen them in late September. To generalize, I would say that whitefish spawn in the North from the end of September until the end of November. "The spawning habits of Lake Trout are much the same. They too vary from one location to another. At Close Lake and on the Waterfound River they began September twentieth, never earlier. In the bay north of my cabin on Close Lake, they arrived about two weeks later. Trout do not spawn for long, only a few days, and never for more than a week. There is much reference made in the diaries to Fred's dogs. He notes that they are tired at the end of the day, or that he has found them in good condition when he returns from a long moose-hunting trip in the fall. He records any trouble they gave, and their final disposition, when they are no longer fit for the trail, by a shot through the head. In 1947: "I pensioned off the old codger. I did not like the job." In 1948: "Lagoof passed away in the night. I am very sorry to lose such a good dog." In 1952: "I had to dispose of Bozo, one of the most willing dogs I have ever owned. He was about eleven years old." And in 1956: I got bitten by a dog today. I hope the bastard does not have rabies." A few days later there is this entry: "I shot that dog. He was giving me too much trouble and we were not getting along. He would not let me catch him."

The first ice of the season is laid in the narrows. Then foxes, wolves and smaller animals will cross over to make early explorations on the other side of the lake. Narrows are also favoured crossings for the migratory caribou in early winter. However, in contrast, the narrows have open holes in midwinter. In the coldest weather, these open holes freeze over; but then heavy snow falls and the ice, insulated by the snow, is melted away underneath by the current. One cannot travel over the ice in a narrows at any time with any degree of safety, for the ice is always rotten. As soon as spring comes, the narrows are always wide open, long before the rest of the lake is ice-free, and at this time migratory waterfowl descend in clouds to rest and feed on the open water. On Fred's canoe route from Big River to Poorfish Lake, the first narrows was encountered on Crooked (Cowan) Lake, about twenty miles north of the village of Big River. Fred sometimes camped overnight here with his friend Levi Legitt and learned firsthand the advantages of living at a narrows. Old Levi's specialty was trapping coyotes. In those days the thick, white spruce forest stood like a wall on both sides of the narrows and there was plenty of coyote traffic through and around the narrows every winter. Furthermore, the shores were thickly grown with reeds where muskrats flourished. In the spring, they could be taken in open water in the narrows long before the lake itself was free of ice. The ice conditions here were always treacherous. The narrows froze over in midwinter, and teamsters hauling fish were tempted to cross here on the ice instead of taking the longer bush road around. Some horses were drowned there each winter, and their carcasses could be seen in the spring, lying up on the shore where they had been left by the teamsters, who were required by law, to remove them from the water. The next narrows on Fred's route was Stony Narrows on Cree Lake, long a favourite fishing ground for the Indians. Located at the southern entrance of the lake itself, its deep channel was the main highway for canoe travel. Martin Brustad's cabin, built here to take advantage of the excellent fishing, became a regular stopping place for canoe travellers and dog drivers passing in and out of the North. Martin was always ready to accommodate a weary traveller, but he complained bitterly of guests who expectorated into his woodbox and blew their noses in the same receptacle. The narrows that figures most largely in Fred's diaries, and in his life, is the one at the north end of Poorfish Lake. It is obvious that this is Fred's favourite location, and was the site of his first cabin on the lake. For him, life centred around this spot. He has left it from time to time, and once he did not live there for a period of fifteen years, but he has always returned. Fred has expressed in his diaries his growing concern for the future of the barren-ground caribou. In his first years in the North, the herds were so numerous that few gave any thought or credence to the possibility that they could ever become an endangered as a species.

The next winter some caribou came back. Fred writes that he saw "a lakeful" that winter, a herd large enough to cover the surface of a lake. But in 1954 he writes: "The caribou herds are dwindling more and more each year." and after that, the diary references to caribou fall off. One winter Fred considers it worth recording that he has seen some caribou tracks, although in the winter's previous the whole country had been teeming with the northern migrants. When we first met, Fred told me: "Back about 1929, there were caribou all through that country. You saw them in herds of 40 to 100 and you saw them constantly, feeding in the moss beds or resting on the ice. By 1971, I saw none as a rule. The rare sightings were of groups numbering two or three, and, on a very rare occasion, up to ten. " I am sure the bushfires have much to do with cutting off the food supply of caribou and affecting them in a harmful way. The reindeer moss has been burned off over such a vast area that the country could not support the great herds if they did come back. From my own observations, I know it takes forty years to restore the moss after it burns off." |

| Deep River Fur Farm |

| Deep River Trapping Page |

| Deep River Fishing Page |

| My Norwegian Roots |

| Early Mink People Canada - Bowness |

| The Manager's Tale - Hugh Ross |

| Sakitawak Bi-Centennial - 200 Yrs. |

| Lost Land of the Caribou - Ed Theriau |

| The History of Buffalo Narrows |

| Hugh (Lefty) McLeod, Bush Pilot |

| George Greening, Bush Pilot |

| Timber Trails - History of Big River |

| Joe Anstett, Trapper |

| Bill Windrum, Bush Pilot |

| Face the North Wind - Art Karas |

| North to Cree Lake - Art Karas |

| Look at the Past - History Dore Lake |

| George Abbott Family History |

| These Are The Prairies |

| William A. A. Jay, Trapper |

| John Hedlund, Trapper |

| Deep River Photo Gallery |

| Cyril Mahoney, Trapper |

| Saskatchewan Pictorial History |

| Who's Who in furs - 1956 |

| Century in the Making - Big River |

| Wings Beyond Road's End |

| The Northern Trapper, 1923 |

| My Various Links Page |

| Ron Clancy, Author |

| Roman Catholic Church - 1849 |

| Frontier Characters - Ron Clancy |

| Northern Trader - Ron Clancy |

| Various Deep River Videos |

| How the Indians Used the Birch |

| Mink and Fish - Buffalo Narrows |

| Gold and Other Stories - Richards |

"For seventeen winters I camped out," he said to me, an understatement that is full of meaning. Out in the worst weather the country had to offer, often huddled shivering by the campfire at night, often hungry. It did not age him prematurely. Another photograph, marked "Reindeer Lake 1945," shows Fred with his wife, Nora. He is standing among several sleigh dogs, a hand-rolled cigarette in one corner of his mouth. He looks mature now, and his chest has deepened; one might guess that he is thirty-five years old, instead of his actual forty-five. When I first saw Fred in 1971, his hair was sparse, but he was neither bald nor grey. A casual observer might have taken him for sixty or sixty-five, instead of seventy-one. I thought it somewhat unusual that he had, for some years, qualified for the Old Age Security pension and was, at the same time entitled to draw Family Allowance benefits on behalf of his twin sons, then fifteen years old. From Fred's diaries and Ed's journals, I have compiled a list of the years Fred actually spent in the wilderness, trapping.

"For seventeen winters I camped out," he said to me, an understatement that is full of meaning. Out in the worst weather the country had to offer, often huddled shivering by the campfire at night, often hungry. It did not age him prematurely. Another photograph, marked "Reindeer Lake 1945," shows Fred with his wife, Nora. He is standing among several sleigh dogs, a hand-rolled cigarette in one corner of his mouth. He looks mature now, and his chest has deepened; one might guess that he is thirty-five years old, instead of his actual forty-five. When I first saw Fred in 1971, his hair was sparse, but he was neither bald nor grey. A casual observer might have taken him for sixty or sixty-five, instead of seventy-one. I thought it somewhat unusual that he had, for some years, qualified for the Old Age Security pension and was, at the same time entitled to draw Family Allowance benefits on behalf of his twin sons, then fifteen years old. From Fred's diaries and Ed's journals, I have compiled a list of the years Fred actually spent in the wilderness, trapping.

One morning, after checking his fish stocks, Fred writes: "A bear ate up about 600 of my fish." That fall there is no further mention of this animal; apparently, he denned up for the winter after that feast. But the next fall he is back to pester Fred again: "I set a rifle for a bear. He sprung the rifle, the luckiest bear I ever became acquainted with. I have fed him for two years now, a remarkable animal, always nosing around the fish cache the moment I go away." A few days later: "That bear set off the rifle again, luckiest bear this side of Hades!" Fred observed that the bear approached the fish cache by several different trails. After it set off the rifle on one trail, it never used that path again. There remained a third trail. Fred took great pains in setting the rifle this time, reasoning that he had been aiming the rifle at the wrong angle. After he had the set completed, it occurred to him that the line attached to the trigger should be a bit higher. He was sure that the safety button on the rifle was still at "on"; he grabbed the string and raised it slightly to string it over a higher branch. "That bullet passed so close to me that I felt the gas from the muzzle blast in my face," Fred writes, describing a very close brush with death. "There was a strong smell of powder."

One morning, after checking his fish stocks, Fred writes: "A bear ate up about 600 of my fish." That fall there is no further mention of this animal; apparently, he denned up for the winter after that feast. But the next fall he is back to pester Fred again: "I set a rifle for a bear. He sprung the rifle, the luckiest bear I ever became acquainted with. I have fed him for two years now, a remarkable animal, always nosing around the fish cache the moment I go away." A few days later: "That bear set off the rifle again, luckiest bear this side of Hades!" Fred observed that the bear approached the fish cache by several different trails. After it set off the rifle on one trail, it never used that path again. There remained a third trail. Fred took great pains in setting the rifle this time, reasoning that he had been aiming the rifle at the wrong angle. After he had the set completed, it occurred to him that the line attached to the trigger should be a bit higher. He was sure that the safety button on the rifle was still at "on"; he grabbed the string and raised it slightly to string it over a higher branch. "That bullet passed so close to me that I felt the gas from the muzzle blast in my face," Fred writes, describing a very close brush with death. "There was a strong smell of powder." When I questioned Fred about this last incident, he showed me his forearm, where there is a three-inch white scar, quite noticeable to this day. After many years of trapping, Fred settled into the country which surrounds Poorfish and Close Lakes. His trails ran generally along waterways, which flow north-eastward, more or less parallel to one another. He recalls: "During my first years in the north I did not make any money, little better than breaking even. It took several years to learn how to travel and where the best fur country was located. I would be away from my cabin for weeks at a time, spending the nights by the campfire. There is so much of what we call 'punk country,' which is newly burned or just plain unproductive. It takes many years to find good trapping country." Throughout the North, there are, in certain lakes, narrow channels which join two segments of the same lake, as an hourglass is joined at the centre. These channels may be quite narrow and deep. These straits are known as "narrows" in the North, and they are of special interest. As sand trickles through the neck of an hourglass, so the lake waters are funnelled through the narrows. These are, without exception, excellent spots to set a fishnet, to troll or to cast with a rod. Wild animals follow the lake shores and finally arrive at the narrows; game trails on either side of a narrows are always well-worn. As a result, a narrows is a favourite spot for Indians to camp or for a trapper to build his cabin. It is significant that Fred's cabins, at both Close and Poorfish Lakes, were built at the narrows.

When I questioned Fred about this last incident, he showed me his forearm, where there is a three-inch white scar, quite noticeable to this day. After many years of trapping, Fred settled into the country which surrounds Poorfish and Close Lakes. His trails ran generally along waterways, which flow north-eastward, more or less parallel to one another. He recalls: "During my first years in the north I did not make any money, little better than breaking even. It took several years to learn how to travel and where the best fur country was located. I would be away from my cabin for weeks at a time, spending the nights by the campfire. There is so much of what we call 'punk country,' which is newly burned or just plain unproductive. It takes many years to find good trapping country." Throughout the North, there are, in certain lakes, narrow channels which join two segments of the same lake, as an hourglass is joined at the centre. These channels may be quite narrow and deep. These straits are known as "narrows" in the North, and they are of special interest. As sand trickles through the neck of an hourglass, so the lake waters are funnelled through the narrows. These are, without exception, excellent spots to set a fishnet, to troll or to cast with a rod. Wild animals follow the lake shores and finally arrive at the narrows; game trails on either side of a narrows are always well-worn. As a result, a narrows is a favourite spot for Indians to camp or for a trapper to build his cabin. It is significant that Fred's cabins, at both Close and Poorfish Lakes, were built at the narrows. Fred, however, was quick to realize the danger. Over the years he saw the great herds of caribou dwindle, helpless to do anything about it. Another trapper once told Fred that he shot eighty animals in a single winter, for the use of his family and dogs, and to bait his traps. Fred knew that the herds could not absorb losses of this magnitude. The numbers of caribou that migrated into the country fluctuated wildly from year to year. As the years passed, Fred observed that the herds were gradually becoming smaller. In 1948: "There are a few thousand caribou around these parts." In 1950: "The caribou are all passing through here and going south, I suppose to see the farmers." The next year: "It seems there will not be many caribou here this winter. I suppose too many were killed last winter when they migrated so far south. You can't kill them off and have them too." And later that winter, in January, Fred bitterly observes: "There are no caribou anywhere in this country. I have seen no tracks in all my travels. This is the first time in all the years I have been here that I have not seen at least some tracks. I suppose the days of the many caribou are gone forever. Man ought to be well pleased with himself. The results which he has desired have almost been attained."

Fred, however, was quick to realize the danger. Over the years he saw the great herds of caribou dwindle, helpless to do anything about it. Another trapper once told Fred that he shot eighty animals in a single winter, for the use of his family and dogs, and to bait his traps. Fred knew that the herds could not absorb losses of this magnitude. The numbers of caribou that migrated into the country fluctuated wildly from year to year. As the years passed, Fred observed that the herds were gradually becoming smaller. In 1948: "There are a few thousand caribou around these parts." In 1950: "The caribou are all passing through here and going south, I suppose to see the farmers." The next year: "It seems there will not be many caribou here this winter. I suppose too many were killed last winter when they migrated so far south. You can't kill them off and have them too." And later that winter, in January, Fred bitterly observes: "There are no caribou anywhere in this country. I have seen no tracks in all my travels. This is the first time in all the years I have been here that I have not seen at least some tracks. I suppose the days of the many caribou are gone forever. Man ought to be well pleased with himself. The results which he has desired have almost been attained."